The Siege of Yorktown, Virginia, the decisive battle in America’s shocking triumph over the mighty British Empire in its War of Independence, began on this day in history, Sept. 28, 1781.

The siege ended three weeks later, on Oct. 19, with the surrender of the British garrison led by Lord Charles Cornwallis.

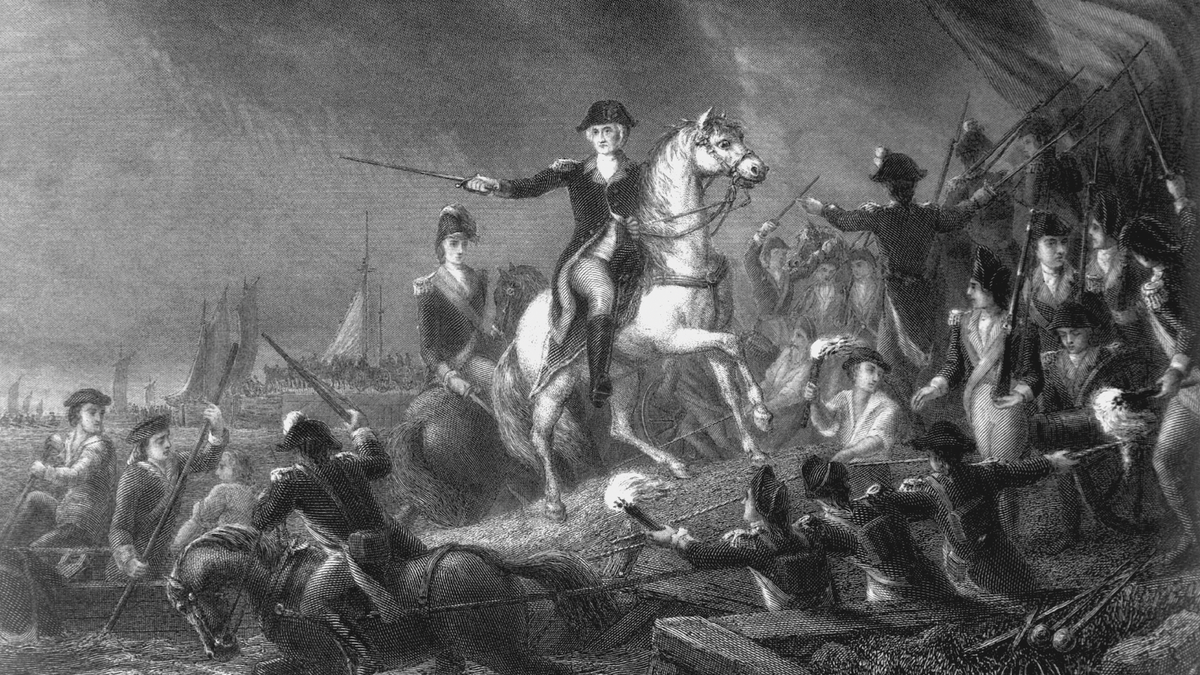

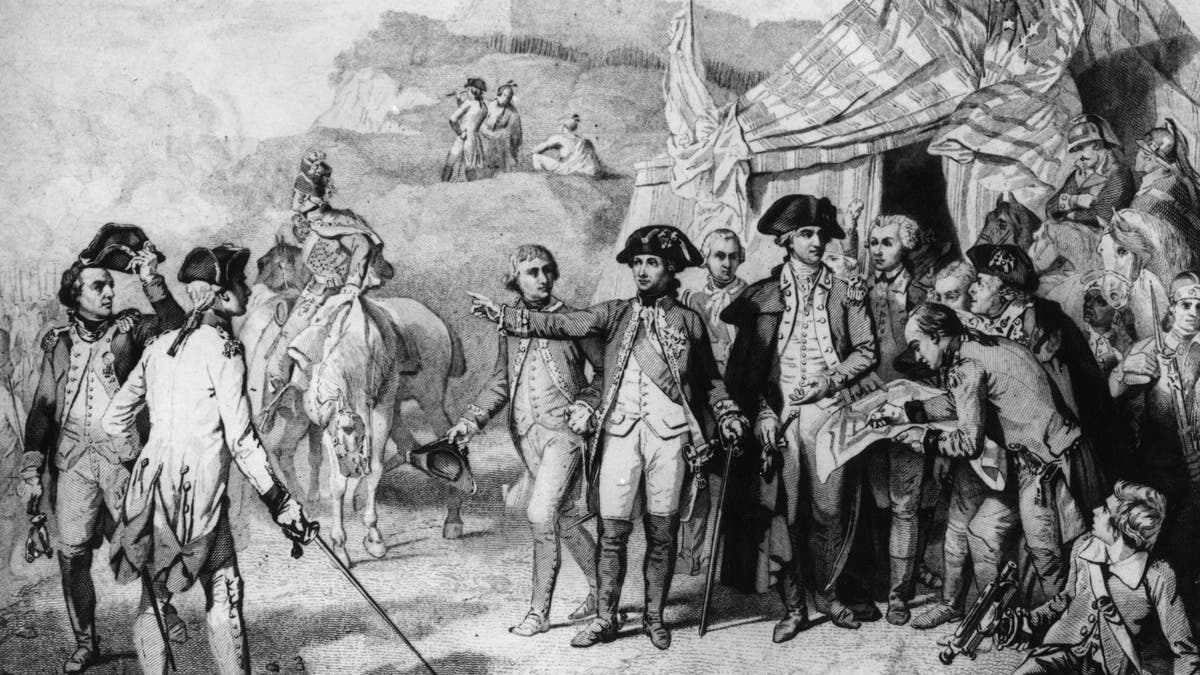

George Washington’s Continental Army and French allies surrounded the Redcoats by both land and sea.

“The British surrender forecast the end of British rule in the colonies and the birth of a new nation — the United States of America,” writes the American Battlefield Trust.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, SEPT. 27, 1779, JOHN ADAMS ASSIGNED TO LEAD PEACE TALKS WITH ENGLAND

The United States had won its daring bid for independence on the battlefield five years after it publicly declared it on paper.

Britain formally recognized American independence almost exactly two years later, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on Sept. 3, 1783.

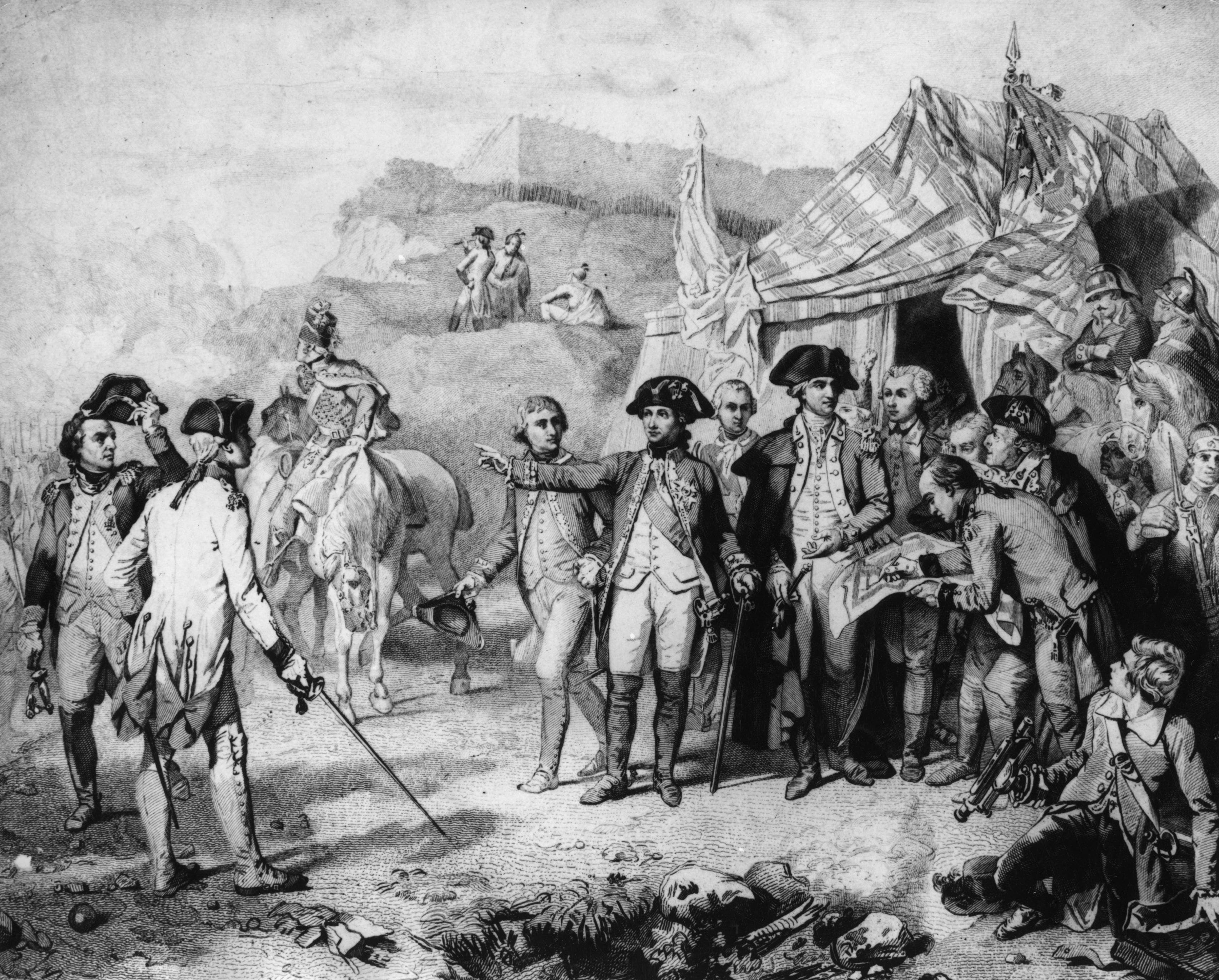

The Americans, aided by French troops under Comte de Rochambeau, set a trap for the outnumbered Redcoats at Yorktown.

Washington’s American forces enjoyed the leadership of another Frenchman, the remarkable Marquis de Lafayette.

Their 19,000 troops, almost evenly split between the allied nations, surrounded about 9,000 Redcoats on a spit of land where the York River meets Chesapeake Bay.

French warships had sailed into Chesapeake Bay just weeks earlier.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, SEPT. 21, 1780, BENEDICT ARNOLD BETRAYS CAUSE OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE

Cornwallis had no way to escape and realized his cause was hopeless. He surrendered with relatively little loss of life considered the forces amassed.

About 800 men were killed or wounded between the combatants, according to the American Battlefield Trust. But the victory for the Americans was overwhelming and decisive.

Cornwallis surrendered his entire garrison.

The American Revolution was over.

The United States had won.

“Washington’s fame grew to international proportions having wrested such an improbable victory.”

The victory required a remarkable bit of logistical and intellectual dexterity by both Washington and Rochambeau.

ON THIS DAY IN HISTORY, SEPT. 19, 1796, PRESIDENT GEORGE WASHINGTON ISSUES FAREWELL ADDRESS

Just weeks earlier, they were working on a long-intended plan to defeat the British under Gen. Henry Clinton in a decisive battle in New York City.

The Redcoats had occupied New York for nearly the entire war after smashing and humiliating Washington’s army in 1776.

“In the spring of 1781, Washington traveled to Rhode Island to meet with Comte de Rochambeau and plan an attack on Clinton,” writes the National Park Service in its history of the Siege of Yorktown.

“A French fleet was expected to arrive in New York later that summer, and Washington wanted to coordinate the attack with the fleet’s arrival. As planned, Rochambeau’s army marched in July and joined with Washington’s troops outside New York City.”

Just weeks earlier, the American and French were working on a long-intended plan to defeat the British in a decisive battle in New York City.

It was only then, in July, that they learned the French fleet was instead sailing into Chesapeake Bay.

Washington quickly devised a cunning new plan to leverage the long-awaited French naval forces and smash Cornwallis’s forces in Yorktown.

“In order to fool Clinton, Washington had his men build big army camps and huge brick bread ovens visible from New York to give the appearance of preparations for a stay,” reports the National Park Service.

For more Lifestyle articles, visit www.foxnews.com/lifestyle

“Washington also prepared false papers under his signature discussing plans for an attack on Clinton, and let these papers fall into British hands.”

With the subterfuge established, Washington and Rochambeau marched for Yorktown in the middle of August, parading past the Continental Congress in Philadelphia in September before reaching Yorktown and setting siege to Cornwallis.

“Washington’s fame grew to international proportions having wrested such an improbable victory, interrupting his much-desired Mount Vernon retirement with greater calls to public service,” writes the library of George Washington’s Mount Vernon.

Read the full article here