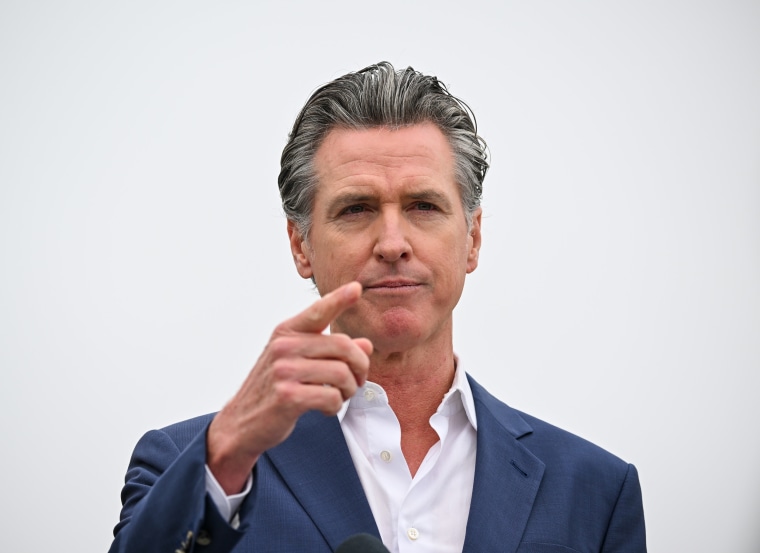

California Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a handful of bills on Thursday that stemmed from a yearslong effort to issue race-based reparations for the state’s Black residents and their descendants. Members of the California Legislative Black Caucus heralded his signature on four bills, including an apology for the state’s role in promoting slavery.

But some advocates — and at least one lawmaker — said the bills do not go far enough to address the generational disparities that slavery inflicted upon Black people.

Sen. Steven A. Bradford was a member of the California Reparations Task Force, which published a sweeping list of recommendations for policies and programs to holistically address the social and financial wrongs of slavery and racial discrimination in the state.

One of his own bills, which would have set up a process for the restitution of land taken through racist tactics, was the only bill in a separate reparations package to make it past the Legislature.

It passed with bipartisan support in the California Senate and Assembly, but was vetoed by Newsom on Wednesday.

In his remarks, Newsom said the bill could not function without the accompanying Freedmen Affairs Agency, which would have been established by another one of Bradford’s bills. Bradford said the Black Caucus blocked that bill from reaching the floor for a vote. “We had enough votes and were at the finish line,” he said in a statement.

Advocates hoping for more ambitious laws to provide a more substantial investment in reparations were sorely disappointed.

The measures passed by the Legislature and signed into law by Newsom, which ranged from banning discrimination based on natural and protective hairstyles to reviewing the list of books banned in prisons, are closer to “racial equity measures,” said Kamilah Moore, a lawyer and the chair of the Reparations Task Force. The policies notably did not require hefty price tags.

Bradford’s bills “represented the strongest recommendations in the report,” she said. They “aligned with the true essence of reparations.”

The task force met from June 2021 to June 2023, conducting research, collecting testimony and ultimately releasing a report with more than 100 policy recommendations to be considered by the governor and the Legislature.

Among these recommendations were the repeal of Proposition 209, a 1996 law banning affirmative action in public agencies, as well as abolishing the death penalty and increasing funding to schools to address racial disparities.

All together, the task force’s recommendations would carry a price tag in the hundreds of billions of dollars. Newsom, who said he had “devoured” the report and had expressed support for reparations generally, set aside $12 million in the state budget to implement any successful measures.

But given California’s multiyear budget deficit, lawmakers expressed concern about the cost of any policies heading to his desk. Bradford said the caucus blocked his bills because they were worried about a potential veto. Newsom’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

The Black Caucus chair, Assemblymember Lori Wilson, said the caucus had concerns about the bills “from the beginning” and that “the governor’s concerns were no surprise to us.”

She declined to comment on what specifically the other concerns were, arguing that any changes would be clear when the legislation would be reintroduced in the next session.

The centerpiece of Bradford’s reparations package was the Freedmen Affairs Agency, which would have overseen state reparations initiatives. The agency was estimated to cost between $3 million and $5 million to run annually, according to a government report.

In the final week of September, at the close of the state legislative session, two dueling reparations packages were expected to be brought to a vote: Bradford’s three bills and six presented by the Black Caucus.

The governor’s office sent a series of substantial edits to Bradford on Sept. 23, which would have replaced the Freedmen Affairs Agency with a research program run out of the state university system.

Bradford rejected the proposed amendments, thinking that he still had the support of his colleagues in the Black Caucus who were supposed to bring his bills to a vote.

By the end of the week, it was clear that members of the caucus had changed their minds and decided to block two of Bradford’s bills, even though they likely had enough support to pass.

By the final hours of the legislative session, dozens of protesters had gathered in the lobby of the Capitol to support Bradford’s bills.

One of these people was Moore, the task force chair, who had driven up to Sacramento from Los Angeles with 20 other people that day. She wanted to show up in person to voice her support for Bradford’s bills. “I wanted to see the process all the way through,” she said.

Organizer Chris Lodgson was another community leader who went to the Capitol to lobby for Bradford’s bills. Lodgson works with a descendant-led organization called the Coalition for Just and Equitable California, or CJEC, which ran community education and feedback sessions on behalf of the task force throughout the state.

“To say we are extremely disappointed is an understatement,” he said. “We felt betrayed by caucus members.”

Last week, Bradford said he had been responding to concerns from a wider community of pro-reparations politicians, including those in the Congressional Black Caucus in Washington, D.C.

National, state and local legislators who had been looking to California as a blueprint for passing progressive reparations legislation were disappointed, Bradford said.

As 16 municipalities, New York state and Illinois develop reparations proposals, California’s task force members have been in touch with a wide network of legislators working on reparations.

Legislators are also discussing the fate of H.R. 40, federal legislation that would establish a commission to study the history of slavery and develop reparations, and the question of who will reintroduce it after the death of U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee this summer.

Read the full article here